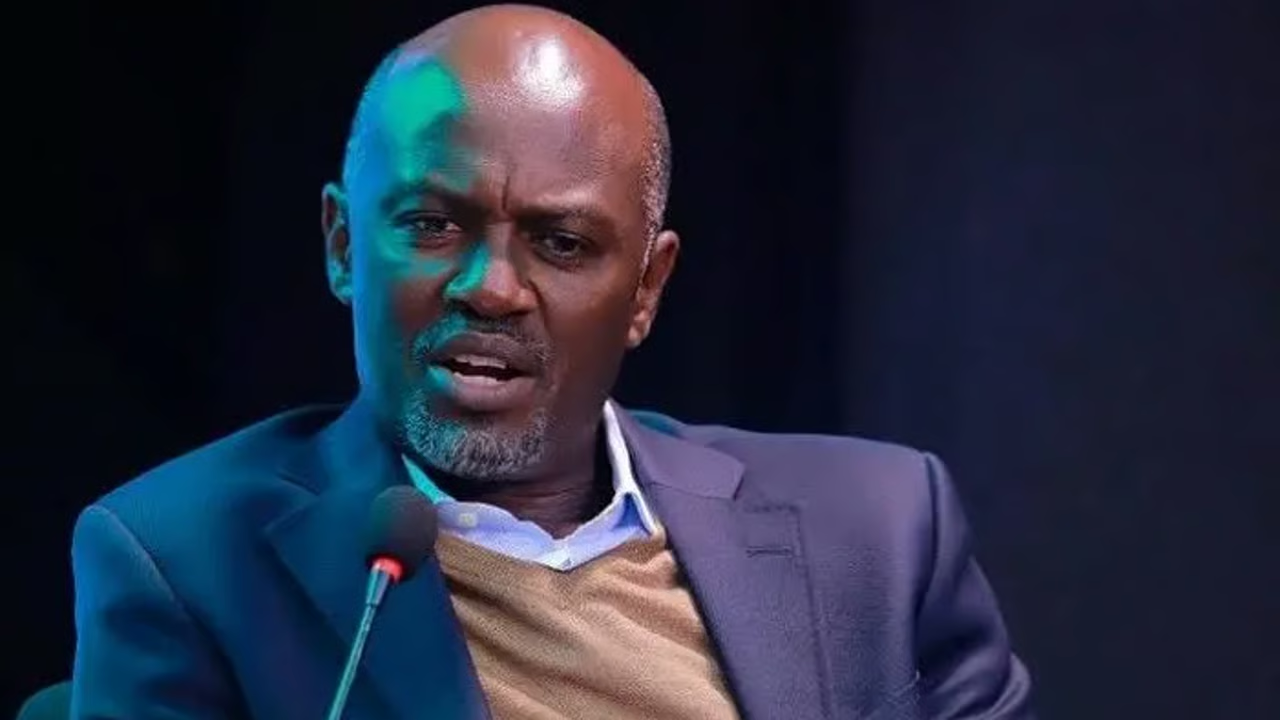

The recent remarks by veteran journalist Andrew Mwenda on Balaalo cattle herders in Northern Uganda, particularly in Acholi, have sparked more storm than clarity.

Mwenda’s distortions of the facts surrounding the Balaalo invasion in a panel discussion on UBC TV on June 25, passes for cleverly inciting ethnic tensions under the guise of promoting national unity.

No wonder that even President Museveni last Sunday dismissed Mwenda’s arguments as disingenuous, misleading and inciteful. He labelled Mwenda a false patriot.

President Museveni was categorical on his microblogging handle X, formerly Twitter, that the orders to evict the Balaalo were not tribal and in no way pits non-Acholi against the Acholi.

President Museveni also described the Balaalo as careless and arrogant herdsmen, with some likely using force of arms to secure land ownership in Acholi.

But Mwenda’s dishonesty, while couched in the language of constitutionalism and nationalism, overlooked the complex, historical, and cultural dynamics that underpin this sensitive issue of war, displacement, dispossession, land grab and ownership.

It was right that Mwenda’s forked-tongue defence of the Balaalo was met with sharp criticisms from co-panelists Prof Ogenga Latigo, and Northern Uganda minister Dr Kenneth Omona, and many more in the Acholi community and beyond.

The ongoing land conflict involving the Balaalo cattle herders in Northern Uganda, particularly in Acholi sub-region, has reignited national debates on land ownership, constitutional rights, and interethnic coexistence.

Clever lie by Mwenda

Mwenda presented several bold claims that sparked outrage. He asserted that all Ugandans have the constitutional right to acquire land and settle anywhere in the country, including in Acholi sub-region.

Mwenda argued that the Balaalo have acquired land legally —either through rental or outright purchase. He also claimed that during his frequent visits to Gen Salim Saleh’s home in Gulu, he never encountered any Acholi landowner who complained about land grabbing by the Balaalo.

Mwenda also argued that the resentment against the Balaalo is rooted in ethnic prejudice and tribalism. He dismissed the distinction between the Balaalo and Acholi as a colonial invention. Mwenda even said the two shared national ancestry.

He also said Asians and some whites own land in Acholi but have not faced the same resistance and outcry that have been directed against the Balaalo. He concluded that the uproar against the Balaalo is therefore not about land, but ethnicity.

On the surface of it, Mwenda’s arguments may appear to defend national integration, but he clothes them with selective evidence, historical inaccuracies, and a troubling disregard for the lived experiences of post-war communities in Northern Uganda.

Mwenda overlooks real land issues

The war between the LRA and government uprooted, displaced and forced out the Acholi into Internally Displaced Persons (IDP) camps. This left vast stretches of land in Northern Uganda unoccupied, uncultivated, and unattended for years.

Many communities returned home and were unable to distinctively locate the boundaries of their ancestral lands. Crucial knowledge of land demarcation—traditionally preserved by elders and natural landmarks, including anthills, trees, and outcrops and wii obur, or old homesteads, — were lost due to the high mortality rate during the war years. At the time, Uganda’s average life expectancy dropped to a mere 47 years by the early 2000s.

In this chaotic context, the land transactions that followed were not acts of free and informed consent but rather often predatory dealings. Land was reportedly sold at throwaway prices as low as Shs250,000 per acre, with land titles issued in as little as one week—raising serious doubts about the legality and transparency of such acquisitions.

These, surely, cannot be treated as standard legal transactions, but exploitations of a people reeling from war, displacement, dispossession, and despondency.

Mwenda’s deceptive urban echoes

Mwenda’s claim that he has not heard complaints from Acholi landowners lacks credibility. He correctly confesses a very narrow scope of his engagements. His narrow perspectives appear to be shaped by conversations held at elite venues at Gen Salim Saleh’s residence in Purongo, others at Acholi Inn, or Boma Hotel in Gulu City, not in the rural communities where the brunt of the conflict is felt.

The real outcries are very loud in the rural areas of Okidi in Atiak, Got Jok in Lamwo, Got Okwara in Nwoya, and Lapul in Pader. Mwenda’s claims of basing his analyses on conversations held far from the angry villagers in the epicentre of conflict is not only flawed but also deceptive.

Balaalo not innocent settlers

Contrary to Mwenda’s narrative, numerous reports indicate that many Balaalo have engaged in harmful practices, including fencing off age-old sacred cultural sites in places like Atiak. They have also obstructed community access to essential water sources, and have engaged in fraudulent land transactions—often marked by forging Local Council (LC) stamps to endorse multiple land transactions for the same piece of land.

Some of the Balaalo also possess identity cards from Rwanda and Burundi, raising legitimate concerns that the influx into Acholiland may involve individuals previously expelled for similar patterns of misconduct from other regions, including Tanzania, Rwanda, and Buliisa District in Bunyoro sub-region.

Weaponising ethnic comparisons

Mwenda’s cheap challenge to the Baganda—asking whether they should then evict non-Baganda like himself from Buganda—misses the essence of the Acholi argument. Mwenda attempts to draw a parallel between peaceful interethnic coexistence and what is perceived in Acholi as fraudulent land encroachment.

Mwenda’s warped argument and deliberate false equivalence between the Buganda and Acholi scenario risks inflaming inter-ethnic tensions rather than promoting understanding.

Such rhetoric does not foster national unity; instead, it risks legitimising land grabbing under the pretext of constitutionalism and dismisses legitimate, culturally-rooted resistance as tribalism. This form of argumentation is divisive rather than reconciliatory.

Acholi hospitality versus exploitation

The Acholi have a well-established reputation for hospitality. Acholi Quarters in Kireka stands as a testament to their openness, where Acholi live harmoniously with the Baganda and other ethnic groups.

Interethnic bonds are further exemplified in cultural settings—such as a Muganda drummer performing on the main drum (Min bul) in the Acholi dance group, Akem kwene.

Furthermore, the Acholi tradition of naming children after individuals from other ethnic groups who are genuinely popular, or have shown kindness—names such as Muteesa, Kaggwa, Katabarwa, and Byaruhanga—demonstrates their inclusive worldview.

But hospitality should not be mistaken for weakness or acquiescence. Defending ancestral lands and demanding justice are not acts of tribalism; they are classic expressions of survival, dignity, and heritage preservation.

Better way forward

The call from Acholi leaders for the Balaalo to go is not for ethnic exclusion but for a fair, transparent, and culturally respectful resolution to the land conflict. Proposals such as those by Dr Kenneth Omona — to first withdraw Balaalo livestock and then verify the legality of land claims—mirror traditional Acholi customs.

In Acholi tradition, when a girl elopes, she is returned to her family before formal marriage negotiations can proceed, and so should it apply to the Balaalo.

Who is inciting ethnic division?

While Mwenda accuses Acholi leaders of ethnicising the Balaalo issue, his interventions may be doing more to inflame tensions. By ignoring well-documented evidence of land fraud, belittling community testimonies, equating criminal encroachment with constitutional freedom, and drawing inflammatory comparisons across ethnic lines, Mwenda risks deepening divisions in a nation still healing from historical wounds.

Demanding accountability in land governance is not a form of tribalism. Protecting cultural and historical spaces is not xenophobia. Celebrating elite deals in the capital while disregarding grassroots voices is not a form of nationalism.

The Balaalo issue is far more than a dispute over cattle and property—it is a question of dignity, justice, and the right of a people to recover and thrive in the aftermath of 20 years of devastation and hopelessness.

Recommendation

To resolve the Balaalo land conflict in Northern Uganda, the government should continue withdrawing Balaalo livestock from contested areas to restore peace. All land transactions must be halted until thorough verification is completed.

A long-overdue livestock compensation scheme should be launched to support affected Acholi communities. Finally, a national dialogue on land justice—free from political and elite interference—must be initiated, centering the voices of the marginalised.

These steps will ensure fairness, restore dignity, and promote lasting coexistence in post-conflict Acholi, Northern Uganda, and other regions.

Anton Latinga Owiny-Dollo Jr is Diaspora-based mental health

clinician and social justice advocate.